10. Many-Electron Systems#

In general, the Schrödinger equation for many-electron systems cannot be solved exactly. For atoms and molecules, even accurate approximations are difficult, and finding more accurate ways to solve many-electron systems, at low enough computational cost to allow interesting and important molecules and their chemical phenomena to be modeled, is an extremely active area of scientific research.

Two Electrons in a Box#

Arguably the simplest possible two-electron system is two electrons confined to a one-dimensional box of length \(a\). The Hamiltonian contains terms for the kinetic energy of the two electrons, the potential that binds each electron, and the electron-electron repulsion between the electrons

where, as before,

In atomic units, this is

and the Schrödinger equation is:

To solve this equation, we need to make approximations. Note that the problem would be easy if the electron-electron repulsion were negligible. Were that the case, the Hamiltonian would be merely the sum of two particle-in-a-box Hamiltonians, one for each electron,

The Schrödinger equation could then be solved by separation of variables, with the eigenfunctions and energies being:

This wavefunction is not quite right, however. Electrons are identical particles, so it is not allowable to label electron 1 with quantum number \(n_1\) and electron 2 with quantum number \(n_2\). Solving this problem, however, requires a consideration of electron spin.

Electron Spin and the Pauli Principle#

Consider a wavefunction for \(N\) identical particles, \(\Psi(\mathbf{r}_1, \mathbf{r}_2, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N)\). We know that the particles are identical, so all observables cannot depend on the specific order in which the particle coordinates are listed. In particular, the probability of observing particles at specified positions cannot depend on which particle is at the specified positions. Ergo,

This means that for any real number \(\eta\),

where \(1^{1/2}=e^{\pi i \eta}\) denotes the square root of unity. A deep result that can be derived from relativistic quantum mechanics but which is far beyond the scope of this course, is that particles have a property called spin. For particles with half-integer spin, \(\eta = 1\); therefore the wavefunction is therefore antisymmetric with respect to exchange of these particles’ spatial and spin coordinates,

This equation is sometimes called the Pauli antisymmetry relation. Particles with half-integer spin are called fermions. Electrons, protons, and neutrons are fermions.

Particles with integer spin are called bosons. Photons are bosons. For bosons, the wavefunction is symmetric with respect to exchange of particles’ positions and spin (\(\eta = 0\)),

Other values of \(\eta\) do not occur for elementary particles, but can appear in some types of exotic physical phenomena. When \(\eta \ne \{0,1 \}\), the particle is called an anyon.

The Pauli exclusion principle states that fermions with the same spin can never be at the same location in space; it is a consequence of the Pauli antisymmetry relation. Suppose that \((\mathbf{r}_j,\sigma_j) = (\mathbf{r}_k,\sigma_k)\). Substituting this into the Pauli antisymmetry relation, we have that a wavefunction is equal to its negative,

The only number that is equal to its negative is zero, which indicates that the wavefunction (and ergo the wavefunction squared) is zero when two fermions with the same spin are at the same location.

Electrons are fermions, and they have total spin of \(\tfrac{1}{2}\). Recall the angular momentum operators and eigenfunctions we learned about with spherical systems. The spherical harmonics were eigenfunctions of the total angular momentum squared and the angular momentum about a specified axis (usually chosen to be the \(z\) axis),

Spin is also a type of angular momentum, and is governed by the same precepts. With some abuse of notation, we can denote spin eigenfunctions as if they were spherical harmonics,

For electrons, protons, and neutrons, the total spin quantum number is \(s=\tfrac{1}{2}\), and the magnetic spin quantum number for the \(z\) axis is \(m_s \in \left\{-\tfrac{1}{2}, \tfrac{1}{2}\right\}\). For convenience, electrons with \(m_s = \tfrac{1}{2}\) are usually said to be “up spin” or \(\alpha\) spin electrons; electrons with \(m_s = -\tfrac{1}{2}\) are usually said to be “down spin” or \(\beta\) spin electrons. So:

In cases where no specific choice of spin is made, one usually uses the generic notation \(\sigma \in \left\{\alpha,\beta \right\}\)

Two Electrons (with Spin) in a Box#

In order to describe two-electron systems, we need to embellish the electronic positions with spin coordinates. Going back to the wavefunction of two noninteracting electrons in a box, we have:

Note that there are now four quantum numbers. As before, this reflects the dimensionality of the system, because there are two principle quantum numbers (corresponding to the spatial coordinates \(x_1\) and \(x_2\)) and two spin quantum numbers (corresponding to the spin coordinates, \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\)).

While this wavefunction solves the Schrödinger equation, it does not satisfy the Pauli antisymmetry relation because it assigns electron one to a specific spin \(\sigma_1\) and principle quantum number \(n_1\). To fix this problem, we can explicitly antisymmetrize the wavefunction,

The factor of \(\tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\) is a normalization constant.

📝 Exercise: Confirm that the wavefunction we just defined \(\psi_{n_1,m_{s,1},n_2,m_{s,2}}(x_1,\sigma_1;x_2,\sigma_2) \) is normalized and satisfies the Pauli antisymmetry relation and the Pauli exclusion principle.#

Two-Electron Atoms#

In a two-electron atom, there are five terms in the Hamiltonian: the kinetic energy of both electrons (2 terms), the potential of attraction between the electron and the nucleus (2 terms), and the electron-electron repulsion potential (1 term).

Here we introduce the notation

and

As with other many-electron systems, solving the Schrödinger equation exactly is impossible. However, if one neglects the electron-electron repulsion term, then the Schrödinger equation reduces to

Solving this equation by separation of variables gives:

Perturbative Treatment of the 2-electron atom#

The energy and wavefunction obtained by totally neglecting the electron-electron repulsion are woefully inaccurate. (E.g., the ground-state energy of the Helium atom is too small by \(\sim 3000 \text{kJ/mol}\) if you neglect the electron-electron repulsion. We can attempt to account for the effects of electron-electron correlation with perturbation theory. The Hamiltonian of interest, in atomic units, is

\(\hat{H}(0)\) is the exactly solvable Hamiltonian we considered in the previous section. \(\hat{H}(1)\) is the exact Hamiltonian of a 2-electron atom (with interacting electrons). The first-order correction to the ground-state energy can be evaluated from the Hellmann-Feynman theorem as:

This evaluation of this integral is rather complicated, but detailed instructions are provided here.

To first order, then, the energy is:

For the Helium atom, this gives an energy

A more detailed derivations of this result is included in the pdf.

Variational Treatment of the 2-electron atom#

The ground-state wavefunction for the 2-electron atom, with electron-electron repulsion excluded, is

where

However, we know that one effect of the electron-electron repulsion is that the nucleus is screened. That is, electron 1 feels a reduced attraction to the nucleus because of its repulsion to electron 2. Obviously when the electron is very close to the nucleus, it feels the full nuclear charge (\(Z_{eff}(0) = Z\)) and when an electron is far from the nucleus, the nuclear charge is reduced one because of the other electron (\(Z_{eff}(\infty) = Z-1\)). This suggests using an orbital like:

{where \(\zeta(r)\) is chosen to minimize the energy. When this is done, and the variational principle is invoked to minimize \(\zeta(r)\), one is doing a Hartree-Fock calculation on the two-electron atom. I.e., \(E_{\text{Hartree-Fock}} = \min_{\zeta(r)} \braket{\Psi(\zeta(r))|\hat{H}|\Psi(\zeta(r))}\). So, for the ground state of the Helium atom, one has:

Hartree-Fock is too difficult to solve by hand. Consider a very simple model, where the effective nuclear charge is chosen to be a constant, which “averages” somehow the values the effective nuclear charge should have near to, and far from, the nucleus. I.e., one picks a single value of \(Z-1 \lt \zeta \lt Z\). The orbital is then

The integrals one needs can be evaluated relatively easily using the Hellmann-Feynman theorem, see the detailed derivation. The final result is the energy expression,

According to the variational principle, \(E(\zeta) > E_{\text{Hartree-Fock}} > E_{\text{accurate}}\). The best result will be obtained by minimizing this expression with respect to \(\zeta\). Setting

So the optimal effective nuclear charge was

and substituting this back into the expression allows us to further augment our results for the ground state energy of the Helium atom:

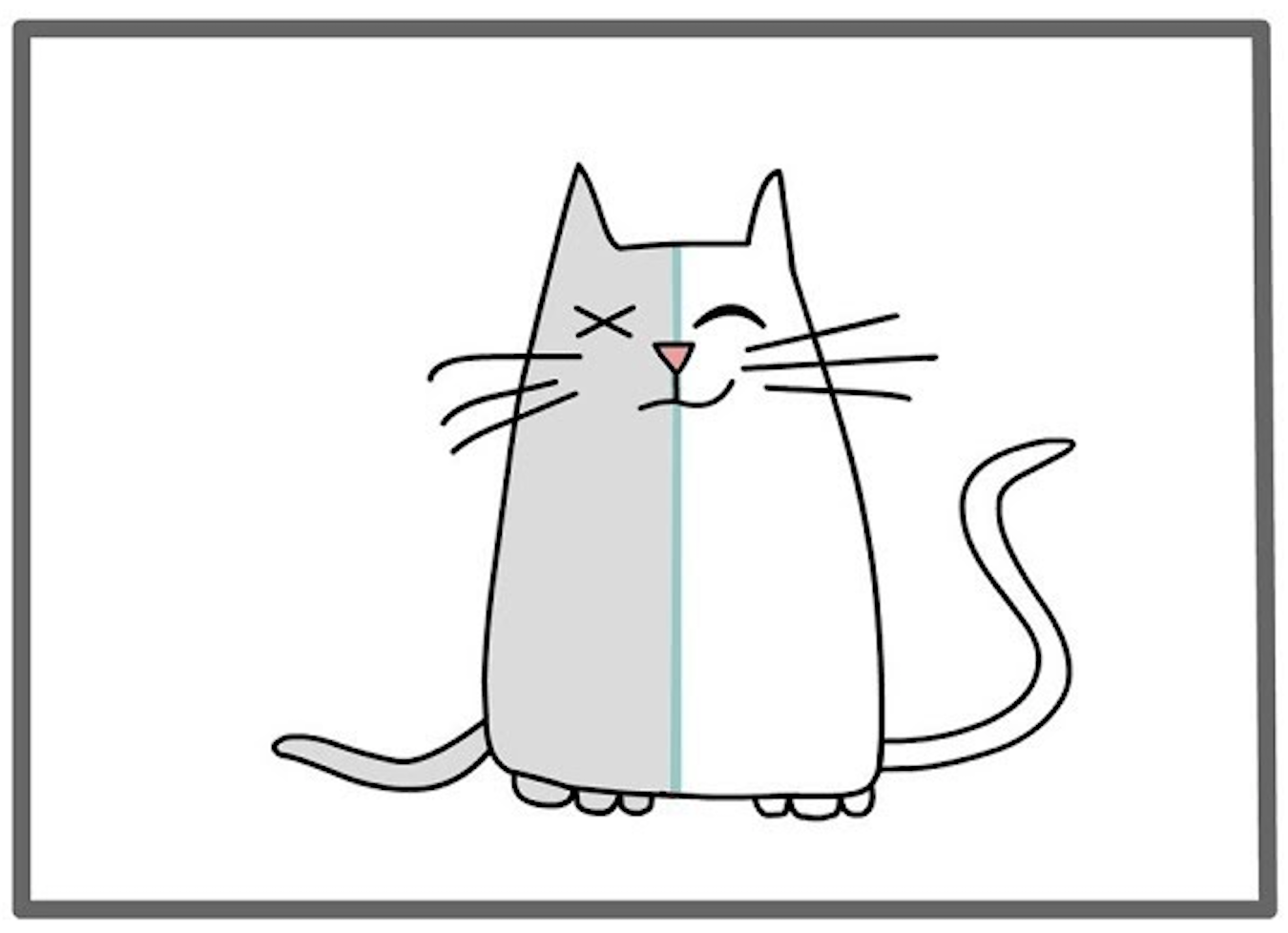

Many-electron wavefunctions: the Slater Determinant#

For more than two electrons, explicitly antisymmetrizing the wavefunction becomes extremely tedious. For example, for a 3-electron system, with electrons in the spatial orbitals \(\phi_1(\mathbf{r})\), \(\phi_2(\mathbf{r})\), and \(\phi_3(\mathbf{r})\), the antisymmetrized wavefunction is:

In general, for an \(N\) electron wavefunction, there are \(N!\) terms in the antisymmetrized product.

It is helpful to introduce a more compact notation. The product of a spatial orbital and a spin eigenfunction is called a spin-orbital, and denoted

For example, we can then rewrite the 3-electron antisymmetrized product as:

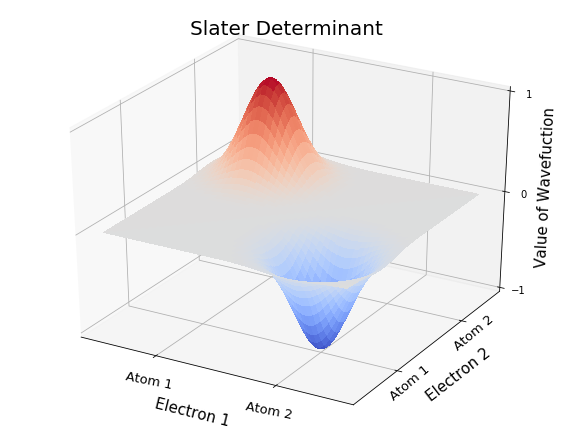

or as a Slater determinant

To exemplify the notation, let’s write a Slater determinant for the ground-state electron configuration of the Beryllium atom, \(\text{1s}^2\text{2s}^2\).

The first row of this determinant indicates that the first electron can be in the 1s or 2s orbital, with spin up or spin down. Similarly, the second row of the determinant indicates which orbitals/spins the second electron can have. The first column of the determinant indicates that the up-spin 1s orbital can be occupied by the first, second, third, or fourth electron. Similarly, the last column indicates that the down-spin 2s orbital can be occupied by the first, second, third, or fourth electron.

In general, for an \(N\)-electron system with occupied spin-orbitals \(\phi_1, \phi_2, \ldots \phi_N\), the Slater determinant is:

Because all the key information in the determinant can be inferred from the first row, we often abbreviate the Slater determinant with

The Slater determinant captures the Pauli antisymmetry relation because when you interchange two rows of a determinant (corresponding to interchanging the coordinates of two electrons) the determinant changes by a multiplicative factor of -1. Similarly, the Pauli exclusions principle is satisfied because when two electrons are at the same location, two rows of the determinant are equal, and the determinant is zero. In addition to the (spatial) Pauli principles, the Slater determinant indicates that you cannot put two electrons in the same spin-orbital (because the determinant is zero if two columns are the same). The ability to satisfy these key mathematical properties of fermions with a compact wavefunction form is why the Slater determinant is certral to practical quantum chemistry.

Incidentally, for bosons the situation is similar, but instead of a Slater determinant one has a Slater permanent. A permanent is similar to a determinant, but when rows (or columns) are interchanged, the permanent of a matrix does not change. Unfortunately, permanents are much more difficult to evaluate, computationally, than determinants.

📝 Exercise: By explicit evaluation, confirm that the \(2 \times 2\) and \(3 \times 3\) Slater determinants recover the result that would be obtained by explicit antisymmetrization.#

📝 Exercise: Write a Slater determinant for the lowest-energy pentuplet state of the Carbon atom, with electron configuration \(\text{1s}^2 \text{2s}^1 \text{2p}_0^1 \text{2p}_{+1}^1 \text{2p}_{-1}^1\). Assume all unpaired electrons have \(\alpha\) spin.#

Example: Many electrons in a Box#

The Hamiltonian for \(N\) electrons confined to a box is, in atomic units,

where, as usual,

To solve the Schrödinger equation, we neglect the electron-electron repulsion energy. The resulting Hamiltonian is:

The ground-state energy and wavefunction is obtained by occupying the lowest-energy one-electron states. If the system is closed-shell, then \(N\) is even, and the ground-state wavefunction and energy are estimated to be merely,

where

The lowest-energy excitation energy of a particle-in-a-box is obtained by exciting an electron from the highest-occupied orbital,

to the lowest unoccupied orbital,

The Slater determinant and energy of the lowest-energy excited state is then:

where, as before, we’ve assumed that electron-electron repulsion is negligible. This is reasonable for a sufficiently large box, where electrons can space themselves far away from each other.

There are seemingly two equivalent excited states, depending on whether the \(\alpha\) or \(\beta\) electron is excited. In practice, however, this state is not a singlet. To form a singlet state, one takes a linear combination of these two choices:

Notice that for an arbitrary state, the (noninteracting) energy is just the sum of the occupied orbital energies. If \(n_k\) denotes the number of electrons in a spatial orbital, then

📝 Exercise: Write the Slater determinant for, and an approximate energy expression for, the ground state and first excited state of 2 electrons in a 2-dimensional square box and 2 electrons in a 3-dimension square box. What changes when you repeat the exercise for 3 electrons?#

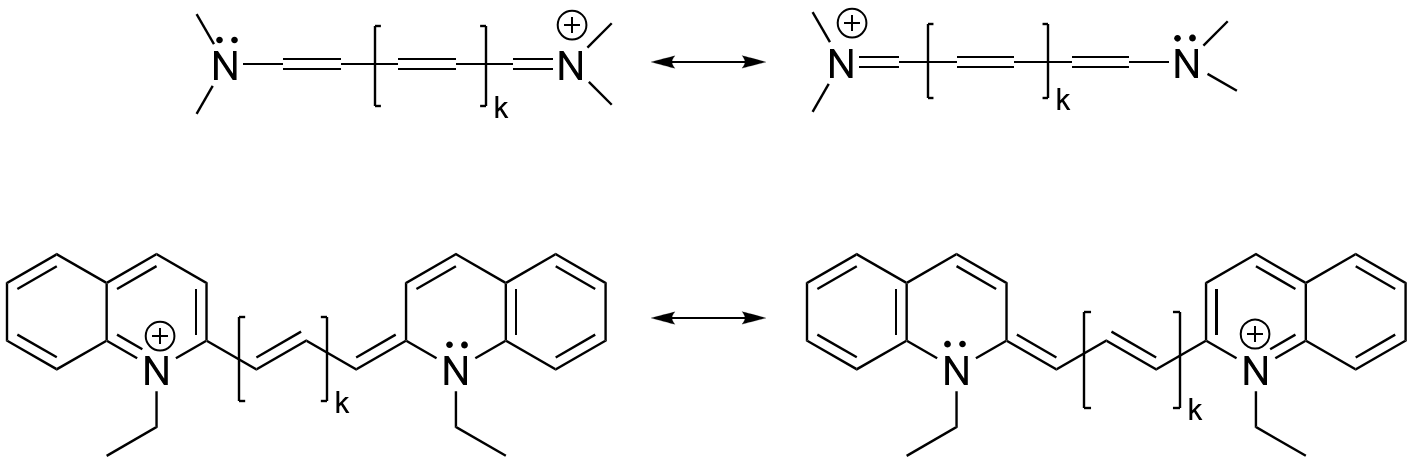

Example: Spectroscopy of Cyanine Dyes#

We are now, finally, in position to revisit the spectrum of the cynanine dyes we began our treatment of quantum mechanics with. Recall that for the cyanine dyes, we can approximate the length of the box with

and the number of conjugated \(\pi\)-electrons is:

The excitation energy is then:

The wavelength of the transition is given by finding the frequency of the transition. Because we are working in atomic units, it’s easier to first compute the angular frequency, which is just equal to the energy difference (in atomic units),

Then from

we have

where the speed of light, in atomic units, is 137.036.

The following code block computes the excitation energies for cyanine dyes of a given length, \(k\).

import ipywidgets as widgets

import math

# Define a function for the wavelength associated with the

# lowest-frequency excitation of a cyanine dye with

# specified value of k

def compute_wavelength(k):

"Compute absorption wavelength of a cyanine dye with 2k+6 pi electrons in nm."

# length of box:

a = 10.71 + 4.71 * (k + 1)

# angular frequency of absorption and excitation energy are the same in a.u.

omega = math.pi**2 * (2 * k + 7) / (2 * a**2)

# compute absorption wavelength in Bohr (a.u.)

lambda_au = (2 * math.pi * 137.036)/omega

# convert Bohr to nanometers

lambda_nm = lambda_au * 0.0529177

return lambda_nm

print("For a cyanine dye, there are 2k+6 conjugated pi electrons in the box.")

print("For reference, the experimental absorption wavelengths for various k are:")

print("k = 0 (6 pi electrons): 313 nm")

print("k = 1 (8 pi electrons): 416 nm")

print("k = 2 (10 pi electrons): 519 nm")

print("k = 3 (12 pi electrons): 625 nm")

# set up the value k for the size of the dye.

k = 12

def print_wavelength(k):

print(f'The experimental absorption wavelength for k={k} is {compute_wavelength(k):.0f} nm')

print_wavelength(k)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[1], line 1

----> 1 import ipywidgets as widgets

2 import math

4 # Define a function for the wavelength associated with the

5 # lowest-frequency excitation of a cyanine dye with

6 # specified value of k

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'ipywidgets'

Many-Electron Atoms and Molecules#

Detailed notes on many-electron atoms and molecules are available as PDFs.

For a molecule in the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the electronic Hamiltonian for \(N\) electrons at positions \(\mathbf{r}_1, \mathbf{r}_2, \ldots \mathbf{r}_N\) and \(P_{\text{atoms}}\) nuclei at positions \(\mathbf{R}_1, \mathbf{R}_2, \ldots \mathbf{R}_P\) is, in atomic units,

The electron-nuclear potential binds the electrons to the system, and is augmented by additional terms when the molecule is contained in an external field, which can be provided by an experimental apparatus or even surrounding solvent molecules. For this reason, it is common to replace the electron nuclear potential with a more general external potential,

The external potential contains all the potentials acting on the electrons that are not due to the other electrons. The Hamiltonian for any \(N\)-electron system is thus:

The Schrödinger equation for \(\hat{H}_{\text{el}}\) is not solvable because of the electron-electron coupling terms. As we saw for many-electron atoms, neglecting the electron-electron terms entirely is a poor approximation. Recall that the idea of the Hartree-Fock approximation is that electrons are screened; we can therefore replace the detailed pairwise electron-electron repulsion term with an effective internal potential that represents the interactions of the electrons with the cloud of other electrons,

This leads to a decoupled electronic Hamiltonian in which the individual electronic coordinates act (quasi)independently,

The eigenfunctions of this Hamiltonian are Slater determinants of the orbitals that solve the one-electron Schrödinger equation,

and the eigenenergy is the sum of the energy of the orbitals that are occupied in the determinant,

There are many different ways to choose \(w(\mathbf{r})\).

choose \(w(\mathbf{r})\) so that the resulting Slater determinant is as close as possible to the true ground-state wavefunction. (Bruckner)

choose \(w(\mathbf{r})\) so that the resulting determinant has the lowest possible energy. (Hartree-Fock)

choose \(w(\mathbf{r})\) as a local operator so that the determinant has the lowest possible energy. (Optimized Effective Potential)

choose \(w(\mathbf{r})\) so that the electron density and related properties (like the electrostatic potential) are exact. (Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory)

choose \(w(\mathbf{r})\) so that the orbital energies, \(\epsilon_k\), correspond exactly to the energies required to add (unoccupied orbitals) or remove (occupied orbitals) electrons from the system. (Green’s Function methods).

In practice, most quantum chemistry calculations start from a Slater determinant wavefunction, which was induced by a specific choice of \(w(\mathbf{r})\), typically Hartree-Fock. Sometimes further corrections (using variational methods or perturbation theory) are added to the underlying approach.

🪞 Self-Reflection#

When will the orbital approximation be most accurate? Least accurate?

Explain what the Hartree-Fock approximation has to do with the concept of effective nuclear charge.

Can you think of a system where a single Slater determinant would be an extremely poor approximation?

🤔 Thought-Provoking Questions#

When will the orbital approximation be most accurate? Least accurate?

Show that the spin-angular-momentum operators commute with the molecular Hamiltonian? What is the implication of that in terms of the observability of a molecule’s spin.

Derive the Rydberg formula.

An advanced (and approximate) version of the Rydberg formula holds for highly-excited states of most atoms and molecules, and is particularly accurate for excitations from the highest occupied (\(ns\) orbital) of alkali metal atoms. The basic idea is that the excitation energy can be expressed as a formula like the below, where the quantum defect, \(\delta_{l}\), depends on the orbital angular momentum of the state. Can you understand where the below formula for the excitation energy comes from? Why does the quantum defect depend on angular momentum? Why does the quantum defect decrease as the angular momentum of the state increases? (For example, for Rubidium, \(\delta_0 = 3.13\) but \(\delta_2 = 1.35\).) Why does the quantum defect increase for heavier alkali metal atoms? (For example, for Li, \(\delta_0 = 0.41\) but for Cs, \(\delta_0 = 4.13\).)

Can you derive a Rydberg-like formula for the wavenumber of excitations for a particle-in-a-box? How would this formula become more complicated for particles-in-a-box in higher dimensions?

For conjugated linear molecules like the cyanine dyes, the \(\pi\)-electrons are really confined to a 3-dimensional region, but the size of the region that is perpendicular to the conjugation is much smaller. For example, one could consider a 3-dimensional box or a 3-dimension cylinder:

What are the eigenfunctions and eigenenergies for these systems?

Why is the one-dimensional particle-in-a-box model sufficient for describing the spectroscopy of cyanine dyes? How long does the chain need to be (e.g., for what value of \(k\)) before the non-one-dimensionality of the box becomes important? You can assume the following (reasonable-ish) values for the parameters:

The Coulomb potential governing interparticle attraction/repulsion between two particles, with charges \(q_m\) and \(q_n\) and positions \(\mathbf{r}_m\) and \(\mathbf{r}_n\) in a d-dimensional system is given below. Note that these expressions are not the usual inverse power of the distance. Nonetheless, when considering systems like the cyanine dyes or 2-dimensional quantum dots, we usually use the 3-dimensional Coulomb potential. Why?

🔁 Recapitulation#

What are bosons? What are fermions? How do the wavefunctions differ?

Write the Schrödinger equation for a many-electron molecule in the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

What is the fundamental assumption that underlies the orbital approximation?

What is a Slater determinant?

What is the fundamental idea behind Hartree-Fock theory?

How does one use the secular equation to approximate the wavefunction for a many-electron system?

Why are Gaussian basis functions used in quantum chemistry?

How does one compute an excitation energy?

🔮 Next Up…#

Hückel Theory and Its Extensions

📚 References#

My favorite sources for this material are:

D. A. MacQuarrie, Quantum Chemistry (University Science Books, Mill Valley California, 1983)

There are also some excellent wikipedia articles: